When Art and Dance Unite

Whether through costume, set, or shared philosophy, artists have long played a vital role in expanding dance beyond narrative and tradition. Keep reading to learn more about some of the most inspiring intersections of ballet and the visual arts of the 20th century.

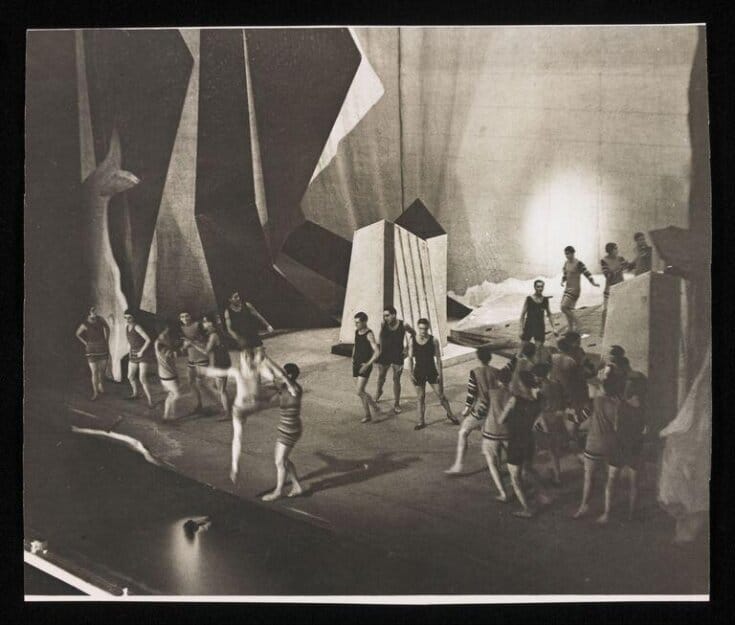

Triadisches Ballett x Bauhaus

Bauhaus, the revolutionary German art school of the interwar period, is best known for its contributions to architecture and design. Bringing together some of the greatest avant-garde artists, including Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Bauhaus championed a cutting edge, minimalist aesthetic. The school’s work encompassed many disciplines, yet you might not know that Bauhaus staged a ballet representing their radically modernist ideas: Triadisches Ballett (Triadic Ballet) by Oskar Schlemmer.

The idea of the ballet was based on the principle of the trinity and it was inspired by modern architecture. Divided into three acts, only three dancers would perform on stage at any given time. Each scene evoked a different mood and featured a distinct colour scheme – also limited to three.

Rather than presenting a traditional narrative ballet, Schlemmer focused on form, geometry, and abstraction. Clad in voluminous, geometric costumes made of foil, wire, rubber and other unsual materials (as well as fabric), the dancers embodied shapes of modern architecture.

Triadisches Ballett premiered in 1922 in Stuttgart, Germany. Following a successful reception, Triadisches Ballet toured nationally and around Europe, before being forgotten until 1968, when it was re-made for German television. It remains as radically modern as it was at the time of its first staging.

Ballets Russes x Pablo Picasso

Founded in 1909 by impresario Sergei Diaghilev, Ballets Russes was one of the most influential artistic ventures of the 20th century. Despite its name, the company never performed in Russia, which at the time was experiencing the turbulences of revolution.

The company attracted some of the world’s finest dancers, choreographers, and musicians, as well as a number of international champions of contemporary art. Diaghilev’s vision was radical: he sought to merge dance, music, and visual art into a unified theatrical experience, engaging the help of the leading creatives of his time.

The one-act ballet Le Train Bleu epitomises this approach: it featured choreography by Bronislava Nijinska, a score by Darius Milhaud, a libretto by French writer Jean Cocteau, costumes by designer Coco Chanel, and a front cloth by Pablo Picasso. Premiering in 1924, this was a light-hearted ballet that captured the spirit of the interwar period and the fashionable lifestyles of the French Riviera elite. Rather than relying on a traditional narrative, the ballet unfolded as a series of stylised vignettes, reflecting the carefree modernity and athleticism that defined the period.

Although known predominantly for his paintings, prints, and sculptures, Picasso has also designed a number of costumes and sets for stage productions, most notably for Ballets Russes. Le Train Bleu includes an enlargement of his painting The Two Women Running along the Beach (The Race) – which was displayed as a front cloth before the performance.

In June 2025, English National Ballet premiered a new version of Le Train Bleu, with choreography our Associate Choreographer Stina Quagebeur. We performed the piece front of the original cloth, dubbed the ‘world’s largest Picasso’, now on display at the newly opened V&A East Storehouse in London. This revival not only celebrates a landmark moment in dance history but also reaffirms the enduring legacy of Diaghilev’s revolutionary vision and its lasting impact.

Martha Graham x Isamu Noguchi

Often referred to as the ‘Mother of Modern Dance’, Martha Graham was a dancer, teacher and choreographer who made a huge mark on 20th century dance. She is best known for her signature movement style, the Graham technique, and her many dance works, where she often evoked spiritual, mythological, or religious imagery.

She regularly collaborated with visual artists to bring her pieces to life, and formed a strong artistic partnership with the sculptor, designer and landscape architect Isamu Noguchi. “I felt I was an extension of Martha”, Noguchi said, “and that she was an extension of me”. Graham stated that “always he has given me something that lived on stage as another character, as another dancer.”

They created some 20 works together. A prominent one is Errand into the Maze, which English National Ballet is dancing this October.

The plot of Errand into the Maze is inspired by the Greek myth of Theseus, in which the hero descends into a labyrinth to kill the Minotaur – a creature that is half-human, half-beast. He is able to do so with the help of princess Ariadne, who equips him with a thread to mark his path. In Graham’s subversive reinterpretation, it is Ariadne who needs to conquer the monster.

The allegorical, introspective dimension of the story is expressed through minimalistic sets designed by Noguchi, He created a large V-shaped sculpture. Evoking both the entrance to the labyrinth and female anatomy, it can be understood as symbolising woman’s journey into the self. The long rope, spread across the stage, represents Ariadne’s thread, but also the labyrinth she descends into.

Errand into the Maze exemplifies the symbiotic nature of their artistic visions: Noguchi’s abstract sculptures provided a physical metaphor for Graham’s metaphysical works, whilst Graham’s choreography gave Noguchi’s static forms a kinetic, narrative life on stage.

Merce Cunningham x Robert Rauschenberg

Robert Rauschenberg’s long-running collaboration with choreographer Merce Cunningham began in 1952 at Black Mountain College, a melting pot for avant-garde artists, when they both participated in John Cage’s Theater Piece No. 1.

Having trained under Martha Graham, Cunningham went on to establish his own dance company in 1953. A prolific choreographer, he created hundreds of works, many of which were collaborations with established artists of various disciplines. He offered his collaborators a lot of creative freedom, believing that no medium should take precedence over another; Cunningham preferred music and visual design to exist as autonomous elements rather than merely supporting the choreography. His radical approach opened dance to abstraction and unpredictability.

Robert Rauschenberg, a pioneer of Neo-Dada and assemblage art, brought a similarly experimental sensibility to visual design. Working with found materials and layered imagery, he rejected traditional distinctions between high and low culture.

Between 1954 and 1964, Rauschenberg contributed to over 20 of Cunningham’s works. In Minutiae (1954), he designed a freestanding Combine sculpture (a layered collage of fabric and wood) that dancers moved around, not in front of. In Story (1963–64), Rauschenberg created “living sets” from found materials, sometimes even painting onstage during performances, echoing Cunningham’s open-form choreography where dancers could alter sequences or costumes in real time.

Though working independently, both artists were driven by a shared interest in everyday life, unpredictability, and collapsing boundaries between disciplines. Their partnership pushed the limits of performance and affirmed the power of artistic freedom within collaboration.

Cunningham went on to work with many visual artists throughout his career, including Jasper Johns, Nam June Paik, while Rauschenberg developed an artistic collaboration with Trisha Brown.

Michael Clark x Leigh Bowery

Michael Clark and Leigh Bowery’s creative partnership in the 1980s and early 1990s was one of the most radical collaborations in contemporary dance.

Classically trained at the Royal Ballet School and with background in Scottish dance, Michael Clark imbued ballet with the spirit of punk, club scene, and queer culture. Quickly established as “British dance’s true iconoclast”, Clark has collaborated with several era-defining creatives, including fashion designer Alexander McQueen and post-punk band The Fall. Perhaps the most well-known, however, is his work with Leigh Bowery, who both designed for and performed in Clark’s productions.

Bowery, a performance artist and designer, brought a provocative aesthetic and theatricality to Michael Clark’s famously subversive choreography. Their collaborations broke the boundaries between high art and underground culture.

Bowery designed costumes for the Michael Clark Company from 1984 to 1992. Some notable collaborations between the two include costumes for Because We Must (the lavishly embroidered, androgynous outfits were inspired by Bowery’s own clubbing clothes) and Hail the New Puritan – a film representing a fictionalised account of Michael Clark’s life alongside Bowery’s avant-garde production design.

Though Bowery died in 1994, his legacy endures in Clark’s aesthetic – provocative, unapologetically queer, and visually fearless. Together, they redefined what contemporary dance could be, ushering in a new era of avant-garde performance rooted in spectacle, transgression, and underground culture.

This autumn, Errand into the Maze will be performed as part of R:Evolution, celebrating a century of modern ballet’s greatest innovators.